Chicago is legendary for the work ethic of its artists. They are known for their prolific output.

Robert Hardy (1903-1976) was a Chicago legend. Andrews was born in Kansas. His mother died when he was young. His father was a traveling physician for Native American reservations. Hardy’s early life was itinerant, following his father through the Midwest. From time to time, he was raised by his grandmother.

When he was barely out of his teens, he landed a job as a reporter in Minneapolis. Due to a fabricated obituary he wrote, Henry Justin Smith, the editor of the Chicago Daily News, offered him a job. Bob Andrews, as he was later known, came to Chicago and helped make history.

Andrews, barely 21 years old, became the editor of Midweek, the Wednesday magazine supplement of the Daily News. He shared an office and became a friend of poet Carl Sandburg, a reporter at the time. While putting out the magazine, the muse struck. Andrews started to write. He contributed short stories to Midweek under a nom de plume.

On a bet, he wrote, typed, and finished a novel in seven days, “Three Girls Lost.” He did this alongside his responsibilities on Midweek and other duties at the Daily News. He typed over 100,000 words in seven days, not counting the rewritten or wasted pages. The book was serialized in the Daily News before it was published. Andrews sold the movie rights for $7500 ($141,900 today) in 1930. Loretta Young and John Wayne starred in the movie.

In 1922, the Daily News owned a large share of what would soon become the WMAQ radio station. WMAQ eventually moved from its original location, the LaSalle Hotel, to the new Daily News Building at 400 W. Madison (2 N. Riverside Plaza). Eventually, WMAQ was bought by NBC and moved to The Merchandise Mart.

Andrews was approached by Anne Ashenhurst (Future wife of Frank Hummert) of Blackett, Sample & Hummert Advertising. Ashenhurst and Hummert were early pioneers in getting companies to sponsor radio shows, especially what would eventually become soap operas. Mrs. Hummert convinced Andrews to write radio scripts for fifteen-minute-long daytime shows.

It is claimed Ms. Ashenhurst invented the successful template for the radio soap opera. She made them famous and a financial success using formulaic stories. Anne Hummert was a pioneer and an advocate of advertising to appeal to women more than men. Robert Hardy Andrews became legendary through this partnership, though his name is long forgotten.

He wrote scripts for “Just Plain Bill” (originally “Bill the Barber”), “Judy and Jane,” “Ma Perkins,” “Skippy,” “The Stolen Husband,” and “Terry and Mary.” His contract required he keep twenty shows ahead at all times. Andrews did all this while holding down his desk at the Daily News and being a man about town.

Andrews settled in the Tower Town neighborhood. Tower Town stretched from the Water Tower, for which it was named, south to the Chicago River, along Michigan Avenue, and west to Wells St. It was a haven for people living a Bohemian lifestyle. Artists, writers, and entertainers of all kinds lived in Tower Town.

When he started making real money from radio, Andrews moved into the Malabry Court, on the rooftop of 669 N. Michigan (Cole Hahn today). The Malabry Court consisted of six small two-story townhouses surrounding a courtyard with a fountain and garden.

Though he did not create the character, Roberts wrote the storylines and scripts for “Jack Armstrong, the All American Boy.” The character was created by a General Mills executive. The shows were used to promote and sell Wheaties cereal. The series ran from 1933 to 1951.

Roberts wrote more books while working at the Daily News and writing radio scripts. “Windfall” would become the radio and television show “The Millionaire.” Roberts was involved in the production of both. “One Girl Found” was a sequel to “Three Girls Lost.”

Roberts wrote on average 100,000 words per week. When there had to be rewrites, edits, or last-minute additions of new characters or storylines, he could produce 20 to 30 thousand words in one day. It was said Roberts had fingers of steel and a posterior of iron.

Andrews eventually left Chicago and went to Hollywood. He wrote screenplays, produced television shows and movies, and became involved in other aspects of the international movie business.

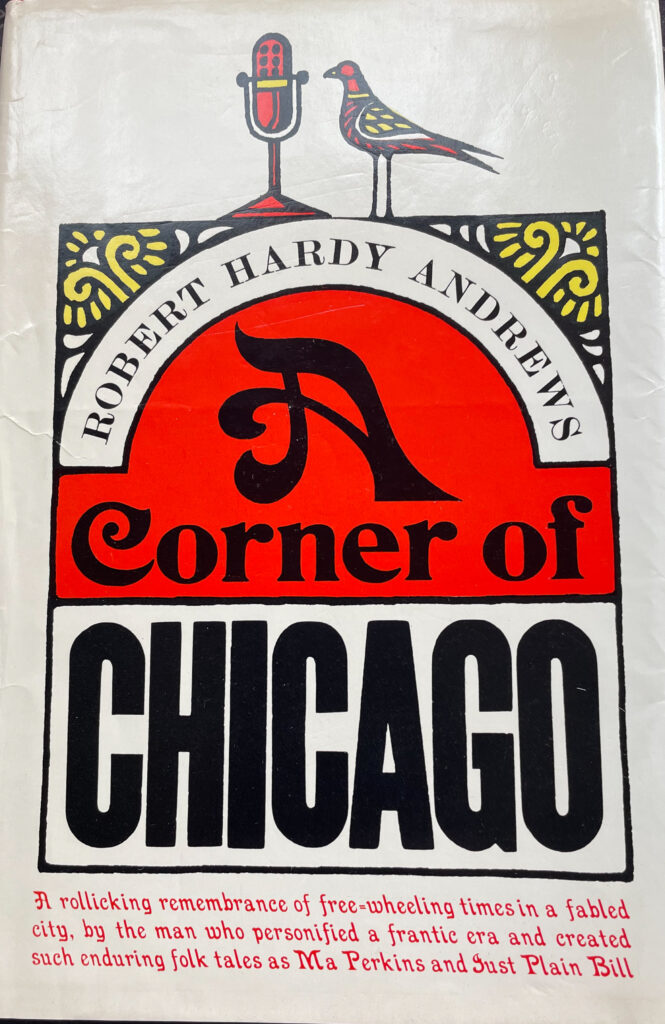

In 1963, Robert Hardy Andrews wrote “A Corner of Chicago,” a biographical sketch of his time in Chicago. The book is a fascinating look at Chicago during the 1920s and 30s and the inner workings of a major newspaper. Robert Andrews idolized Henry Justin Smith and was honored to be a member of the Daily News, “The paper that went home.”

The book describes the characters Andrews came in contact with at the newspaper, on the street, and during his evening carousing in various speakeasies, hotel dining rooms, restaurants, and other places. There are colorful gamblers, saloon owners, pets, and stories about Chicago places long gone, like Tower Town. There are down in the heel actors, raconteurs, rags to riches and riches to rags stories, gangsters, stories of murder and mayhem, and some of the famous and infamous who passed through Chicago lore.

Robert Hardy Andrews died in 1976 in Santa Monica, California.

“A Corner of Chicago” is no longer in publication, though copies can be found on Amazon and eBay.